For decades, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s GRAS rule has allowed untested additives into the food supply. Can RFK Jr. fix it?

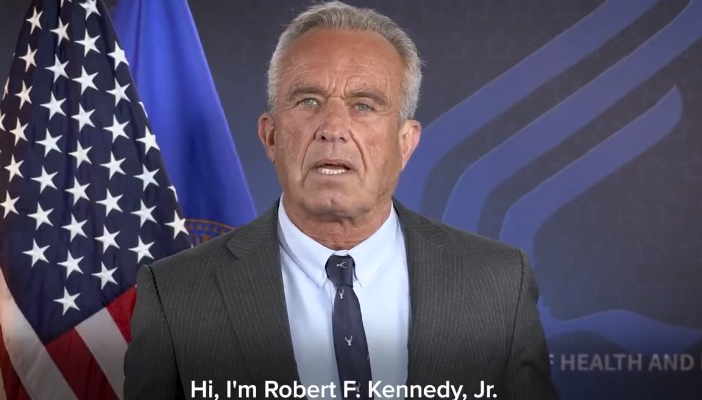

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is making one of his first significant moves as the head of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services by attempting to close a controversial safety loophole within the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

On March 10, Kennedy announced that he is directing “the acting FDA commissioner to take steps to explore potential rulemaking to revise its Substances Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) Final Rule and related guidance to eliminate the self-affirmed GRAS pathway.” This, he shared, “will enhance the FDA’s oversight of ingredients considered to be GRAS and bring transparency to American consumers.”

Here’s what you need to know about the GRAS rule and what Kennedy plans to do about it.

What is the GRAS rule?

As Food & Wine previously reported, the FDA’s GRAS designation allows companies to decide whether the additives they put in their food products are safe for consumption, allowing them to bypass review if it’s “generally” recognized as safe.

In a 2013 report, the Pew Research Center wrote that it was a legal loophole “intended for common food ingredients; manufacturers have used this exception to go to market without agency review on the grounds that the additive used is ‘generally recognized as safe.’” It noted that the FDA interpreted this law as having no obligation “on firms to tell the agency of any GRAS decisions. As a result, companies have determined that an estimated 1,000 chemicals are generally recognized as safe and have used them without notifying the agency.”

And all this is decided by consultants and experts hired by the individual companies, which is a definite conflict of interest.

“The law does not give the FDA the authority it needs to efficiently obtain the information necessary to identify chemicals of concern that are already on the market, set priorities to reassess these chemicals, and then complete a review of their safety,” Pew added. “Moreover, the agency has not been given the resources it needs to effectively implement the original 1958 law.”

According to a 2022 review by the Environmental Working Group, almost 99% of all food chemicals introduced since 2000 were greenlit under GRAS and not via a review by the FDA.